Dmytro Balkhovitin / Shutterstock.com

Fourth of July festivities encompass everything great about summer: backyard barbecues, pool parties, big scoops of homemade ice cream, and watching lightning bugs warm up the sky for terrific fireworks shows. Back in 1776, Founding Father John Adams actually predicted we’d celebrate this way. He told his wife that the holiday would include “Games, Sports, Guns, Bells, Bonfires and Illuminations from one End of this Continent to the other.” And he was right, for the most part. The one thing he got wrong, however, was the date. John Adams thought we’d be celebrating Independence Day on July 2.

The colonies’ struggle for independence from Britain was relatively sudden. Although Englishmen had been settling the colonies for over a century (in 1620, the Mayflower was the first ship to arrive from England), relations with Britain soured in the mid-1760s when it began imposing taxes on the colonies.

It wasn’t that colonists weren’t willing to pay taxes—they were; it was that Britain refused to give the colonists a voice in Parliament. In other words, the colonies had to pay British government, but they had no say in British government. That right there is taxation without representation, and the colonists wouldn’t stand for it. Protests broke out.

At this point, most colonists hoped Britain would respond to the protests by giving political representation to the colonies, but others, like feisty John Adams, believed that independence was inevitable (although he did not publicly admit this just yet). He was giddy when he received news about the Boston Tea Party, a protest during which colonists destroyed an entire shipment of taxable tea by dumping it into the Boston Harbor. “This Destruction of the Tea is so bold, so daring, so firm, intrepid and inflexible, and it must have so important Consequences, and so lasting, that I cant but consider it as an Epocha in History,” Adams wrote in his diary.

Not everyone was thrilled. Ben Franklin thought the colonies should reimburse Britain before the situation escalated, for example, but Britain was already furious. It attempted to punish Massachusetts (and all the colonies) by closing ports, taking away local governments, giving more judicial power to Great Britain, and mandating that the colonies house British soldiers.

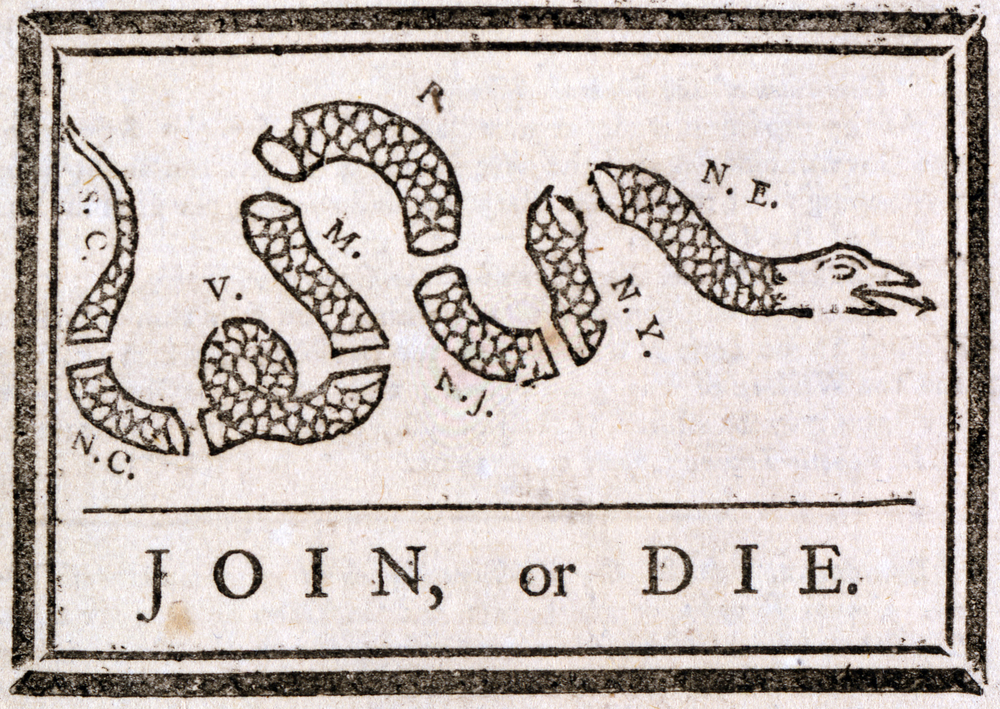

These Intolerable Acts, as they came to be known, added more fuel to the fire, and protests became increasingly violent. A First Continental Congress was organized to discuss independence from Britain. John Adams was vocal about the need, but some delegates still turned a deaf ear to his arguments.

Battles began in 1775 (the Battles of Lexington and Concord were the first, and the Battle of Bunker Hill was a victory shortly after). The Continental Congress reconvened, but many members still hoped to reconcile with Britain. In July of that year, they submitted the Olive-Branch Petition to Britain, which offered a ceasefire in exchange for the recognition of American rights. Britain declined, and the colonies were said to be in open rebellion. Independence, again, became the topic of discussion.

Everett Historical / Shutterstock.com

By June of 1776, the Second Continental Congress heard arguments on the issue of independence. Many delegates were already in favor, so a committee was tasked with writing a statement that explained why the colonies were fighting for sovereignty. Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, and two other delegates were appointed to this Committee of Five, and the former was charged with drafting the document. Meanwhile, John Adams continued to champion independence to the Congress before the final vote. On July 2, it voted unanimously to secede from Britain.

John Adams would remember this date as Independence Day, so why do we wait two more days to celebrate it?

The answer is simple. Though Thomas Jefferson had been laboring to write the Declaration of Independence for the previous two or three weeks, the Congress itself hadn’t made its final edits to the document. It spent the latter part of July 2, all of July 3, and the morning of July 4 adjusting its wording. On that final afternoon, it was approved by the Continental Congress.

The United States had not yet finished fighting the Revolutionary War, but July of 1776 was important: It was then that the colonies declared their intention to be an independent nation.

Enjoy your celebrations this Fourth of July! Watch 1776. Listen to the soundtrack from Hamilton the musical. Snack on your favorite red, white, and blue treats. And be grateful for the roles that John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, the Continental Congress, and the Patriot troops played in the American fight for freedom. We’ve got them to thank for much more than our parades and fireworks shows.

(1776 / Giphy)

-

Everything You Need to Know about December Holidays

-

Simple Halloween Hacks to Fit Every Budget

-

Holiday Movies to Watch while You’re on Winter Break

-

Remembering Martin Luther King Jr.

-

Celebrating Earth Day and Saving the Environment

-

The Biggest Fourth of July Celebrations in America

-

Charities to Get Involved With if You’re Feeling Green for Earth Day

-

Using Your Winter Break Wisely in High School

-

Celebrating Hanukkah, Christmas, and Kwanzaa

-

Cheap Valentine’s Gift and Date Ideas Your Partner Will Love

-

Nine Ways to Have a Productive Winter Break

-

Easy Ways to Contribute to Thanksgiving or Friendsgiving